Big Data for Big Problems - The National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON)

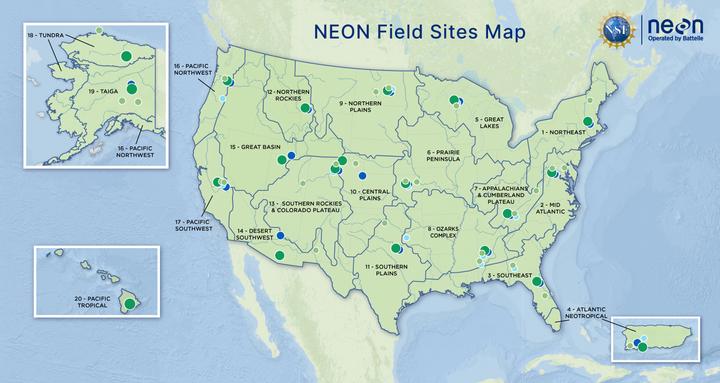

Ecoregions for the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON)

Ecoregions for the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON)Be patient … content still being written

This is one of a multi-part series on my collaboration with the National Ecological Observatory (NEON) project, which is also a major part of my dissertation.

Future posts will include:

- Soil core collection from the NEON sites

- Soil organic matter signatures from NEON sites

- Fire histories of NEON sites - see Twitter thread

Background

Long-term data sets are the holy grail for ecology. In the age of rapid climatic transition(s), knowing how ecosystem currently function may help us predict how they will respond in the future. As with all things ecology, everything is connected and nearly all things interact.

Want to know about bird populations? You need to know about pollinator species and their abundances, where their preferred-plant foods are, and how rain events or topographical factors determine where those plants may survive. In order to study the outward effect of biological systems, you need to have a firm understanding of the abiotic factors first.

These abiotic factors will never make it onto a splashy commercial, but they will determine what wildlife can survive in which locations. Beyond charismatic wildlife, global climate change models depend on robust long-term data that need to be empirically derived. But collecting these data are expensive, which is why federally-funded research is critical.

Long-Term Research

I like to think of NEON as a version 2.0 of the Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) that started in the 1980’s (the National Science Foundation funds both endeavors). The most famous LTER site helped us discover the damage that acid rain was having on Northeastern US hardwood ecosystems. The Hubbard Brook LTER documented strong evidence that acid rain was (1) linked to human emissions and (2) those emissions were harming terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. This research eventually led to the implementation of the Clean Air Act in 1970, and amendments in 1990. Unfortunately, the effects of acid rain deposition have lasting effects, long after the significant decreases in pollution.

Research on these LTER’s continue today. For example, a 2020 publication from Hubbard Brook describes what they’ve learned after decades of cross-disciplinary research:

“hydropedological studies have shed light on linkages between hydrologic flow paths and soil development that provide valuable perspective for managing forests and understanding stream water quality.”

Here you can see how important the LTER research was in the 1980’s, especially how it evolved to look at mechanisms instead of just ecosystem patterns. These LTER sites were unfortunately relatively few in number (in 1980 there were only six, currently there are twenty-eight) and they tended to focus on either the terrestrial or aquatic systems, but not necessarily integrating the two. The version 2.0 would try and rectify some of these limitations.

National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON)

NEON aimed to fill in some gaps that the LTER network accidentally left over. For example, funding for each site was allocated for at least 30-years from its inception, with about 80 sites across North America carefully selected to best represent the larger eco-climatic region. The integration of land and water cycles were well thought out, such that for each terrestrial site there is an associated aquatic site. Furthermore, physical archive samples would be stored for research to request upon, and all observations would be publicly available so anyone in the world could query data from their keyboard (read more on other data streams and field instrumentation that can be installed). Suffice to say the amount of research that will be coming out of NEON’s endeavors will pay dividends for decades to come.

Although I was unable to visit every single NEON site, I did get soil cores that were taken during the installation of the soil CO~2 sensors. You can read a NEON blog post about my research, watch me drop acid on the NEON soils, see photos of very red soils and very cold soils, and even some pyrogenic carbon research.