Moisture-driven divergence in mineral-associated soil carbon persistence

Abstract

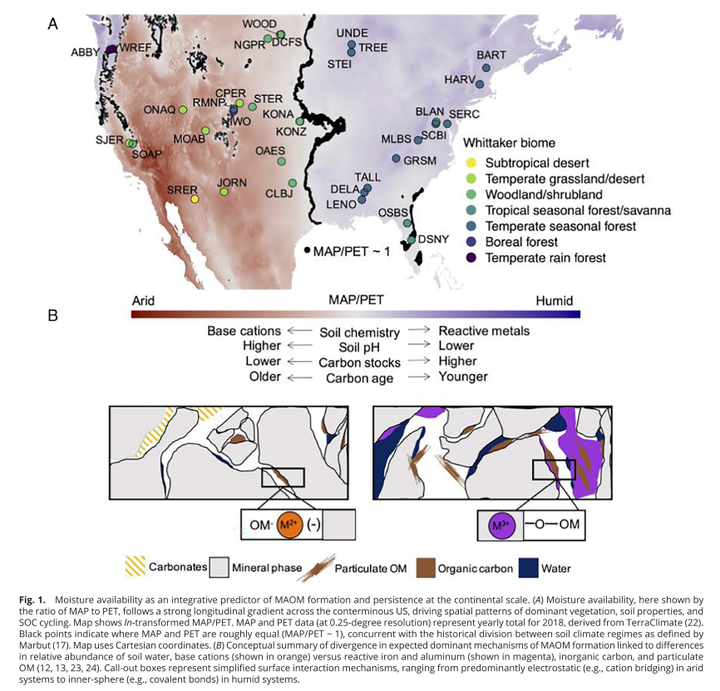

Mineral stabilization of soil organic matter is an important regulator of the global carbon (C) cycle. However, the vulnerability of mineral-stabilized organic matter (OM) to climate change is currently unknown. We examined soil profiles from 34 sites across the conterminous USA to investigate how the abundance and persistence of mineral-associated organic C varied with climate at the continental scale. Using a novel combination of radiocarbon and molecular composition measurements, we show that the relationship between the abundance and persistence of mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) appears to be driven by moisture availability. In wetter climates where precipitation exceeds evapotranspiration, excess moisture leads to deeper and more prolonged periods of wetness, creating conditions which favor greater root abundance and also allow for greater diffusion and interaction of inputs with MAOM. In these humid soils, mineral-associated soil organic C concentration and persistence are strongly linked, whereas this relationship is absent in drier climates. In arid soils, root abundance is lower, and interaction of inputs with mineral surfaces is limited by shallower and briefer periods of moisture, resulting in a disconnect between concentration and persistence. Data suggest a tipping point in the cycling of mineral-associated C at a climate threshold where precipitation equals evaporation. As climate patterns shift, our findings emphasize that divergence in the mechanisms of OM persistence associated with historical climate legacies

TLDR

Soil carbon “sequestration” is all the rage now a days, but very rarely does anyone define the time-frame of “sequester”. Usually folks are only looking at changes to soil carbon content, and assuming those changes are permanent. They are not. Here we show that soil carbon content is de-coupled from how long that soil carbon stays in soil (i.e. having more carbon in soils does not necessary mean that carbon sticks around for longer periods of time).

This pattern is driven by two factors. First is the depth of soil carbon, and second is the energy balance between precipitation and the evapotranspiration potential of a given ecosystem.

The depth of soil carbon is one of the best predictors of how long that carbon will stay in soil. More shallow soil horizons (0-20cm) have shorter turnover times on the order of years to decades. But the deeper you go (20-50cm), the turnover times increase to regularly exceed a thousand of years with the deepest (50-100+ cm) soil horizons generating turnover times of tens of thousands of years. This observation, of depth consistently explaining soil-carbon persistence across North American ecosystems, could only have come to fruition because (this project) was continental in scale and we regularly collected soil cores exceeding 100cm in depth. To the best of my knowledge, there is no other project that spans the X-Y and Z scales like we did.

There was a caveat to depth explaining soil carbon persistence: when ecosystems wanted more water than what nature could provide there was a slight de-coupling in this depth-persistence relationship. Before we get into the details, it’s worth describing exactly what we mean when we say “ecosystems want more water”:

“At the continental scale, soils and hydroclimatic regimes can be bifurcated into two categories based on moisture availability. In water-limited systems (referred to here as arid), evaporation is limited by moisture availability, and the ratio of mean annual precipitation (MAP) to potential evapotranspiration (PET) is less than one (MAP/PET < 1). In energy-limited systems (referred to here as humid), evaporation is limited by available evaporative energy (MAP/PET > 1). In the conterminous USA, this threshold lies near the 98th meridian and approximately 635 mm annual precipitation”

— See 3rd paragraph in Heckman et al., 2023

To extend this concept, if a site is arid (most of the interior Western US) then there is not enough water moving down the soil profile to push that surface carbon into deeper layers. In humid systems (both coasts, and eastern-ish of San Antonio, TX) there is enough precipitation in excess of what plant communities need so there’s plenty of additional water to transport organic matter down the soil profile into deeper layers. You can visualize this arid vs humid framework today at about the 98th Meridian. Furthermore, the availability of water at deeper depths (or lack thereof) facilitates more organic matter-biotic-mineral interactions so the soil chemistry is completely different at 100cm of an arid grassland compared to the same depth of a deciduous forest. Humid sites behave well, in the sense of predicting that - as long as there’s plenty of rain - deeper soils will keep soil carbon stable for longer periods of time.

But here’s the rub, with climate change doing its thing, the area of the US that is expected to become arid is increasing, and thus our ability to predict carbon persistence is also linked with these changes in precipitation patterns. That expectation is already happening! Check out some brilliant explanatory journalism explaining how researchers were investigating this arid/humid divide (emphasis mine):

“the team determined that because of climate change, the humid/arid dividing line once located at the 100th Meridian has shifted to the 98th Meridian, about 140 miles east, since 1979. The change was caused by rising temperatures from fossil fuel-generated greenhouse gas emissions. Higher temperatures caused more soil moisture to evaporate, and shifting wind patterns have decreased precipitation in the southwest. Climate models adjusted for the particular topography of the American West project that the line will continue its march toward the Atlantic, likely moving an additional two to three longitudinal degrees by the end of the century.”

– Christina Cook for CivilEats, April 2018

Just to recap: arid sites cannot transport carbon deeper in soils, and if you want carbon to be “sequestered” for a climatically-meaningful amount of time, you need that carbon to get to deeper layers via water transport! But climate change has already shifted the arid vs humid dividing line 140 miles since 1979 and it’s going to continue. The unnerving reality that a lot of production agriculture occurs in this transition zone between sometimes needing to supplement with irrigation, to not having enough water even with irrigation (I’m very skeptical that precision ag, green-tech, or soil health practices can enable current levels of production ag in these areas to continue unabated. While precision ag/soil health can help at the margins, expecting the same amount of biomass production without enough water to feed plants is a disaster waiting to happen).

What to do?

Honestly, I don’t really know. Recently, I was doing some side research for grass seed / turfgrass soil carbon cycling and came across this hilarious carbon sequestration rate calculation: “Overall, turf grass systems accumulated SOC at a mean rate of 125 ± 136 $gC/(m^2*yr^2)$ across all studies”, with the authors concluding “This analysis shows considerable agreement across studies and climate regions about the high potential of turf grass to accumulate SOC, to levels that can exceed the quantity of SOC stored under native vegetation." I know for a fact that at least one grass seed company (I’m currently based out of the Willamette Valley known as the “grass seed capitol of the world”) is considering using this turfgrass sequestration number of “125 $gC/(m^2*yr^2)$” as an attempt to suggest their company is carbon neutral. They neglect to add the error on their calculation, which is larger than the estimated effect size. Reminder, soils are incredibly heterogeneous, I know because I’ve dug thousands of soil pits in all kinds of ecosystems.

Imagine you were looking at purchasing a new vehicle and they told you “the car works great, except the speedometer can be 110% incorrect”, would you buy that vehicle? I hope not. In addition to the appalling use of data, grass seed companies will probably neglect the fact that turfgrass requires lots of nitrogen and phosphorous inputs, and in replacing native vegetation they negatively impact pollinators that are already having a bit of a crisis.

Us soil scientists are said to be great “systems thinkers” because we need an understanding of chemistry, biology, physics, hydrology, and geology to make soil system intelligible. But if we only think about things inside the soil pit, we neglect the larger systems that interact with soil that (in my view) have a much stronger control on land management practices and ecosystem patterns. This research paper was the culmination of nearly 10 unique publications that caused our thinking as a team to evolve significantly from when the project started in 2015. I can’t speak for the larger research group, but for me personally I’ve come to understand the water side of the soil equation to be under appreciated.

Precipitation patterns are one of the hardest to predict in global climate change models, but they generally show increasing aridity on either side of the equator. According to the USGS, water demands are only increasing. And for all the talk of soils being “natural climate solution”, I think we need to recognize that current agriculture practices are not all that sustainable, climate is changing faster than our practices, and water-availability is the most central factor driving these changes but it’s the hardest factor to predict. We need to be more humble.

Instead of saying soils can be a “natural climate solution”, we should be admitting that current ecosystem-functions are actively changing such that some of the plant-types/cash-crops present on today’s landscape will not be possible in 15 years. Managing for sustainability doesn’t capture the scale of the problem because it assumes a known and static future climate; but we know extreme weather events are increasing and becoming more common so we need to manage for resilience.

It may seem like semantics, but managing for resilience inherently builds in a type of buffering capacity into ecosystems. These are also trade-offs in how we practice landscape and ecosystem management. It will mean planted forests need to have a diversity of trees that makes future harvesting more difficult and less profitable. To acknowledge the US fire suppression practices of the last ~100 years also means we need fewer tress per acre. Toss in the fact that western drought is expected to continue so the oak-savanna biome will travel future up in elevation encroaching on lower mixed-conifer forests of the Sierra Nevada foothills. I believe managing for resilience requires a more thorough appreciation of a given location’s changing hydroclimatic regime that supersedes the management limitations from soil limitations.

Water availability - and lack thereof - will force us to confront the reality that growing cow food in deserts was never a good idea. I’m currently following the story of the Great Salt Lake drying up as a weathervane for the future. Other active water stories are in the Klamath River Basin, the Colorado River Basin, and the Mississippi River. There are active “soil health” practices happening in watersheds that I named above that aim to maintain current rates of agronomic productivity, but increasing your soil carbon content by 0.04% doesn’t matter if you have no water to irrigate your crops, let alone to drink.

P.S. There were two press advertisements of our journal article. Check out the write-up by Virginia Tech and Oregon State University.