Quantifying impacts of forest fire on soil carbon in a young, intensively managed tree farm in the western Oregon Cascades

Abstract

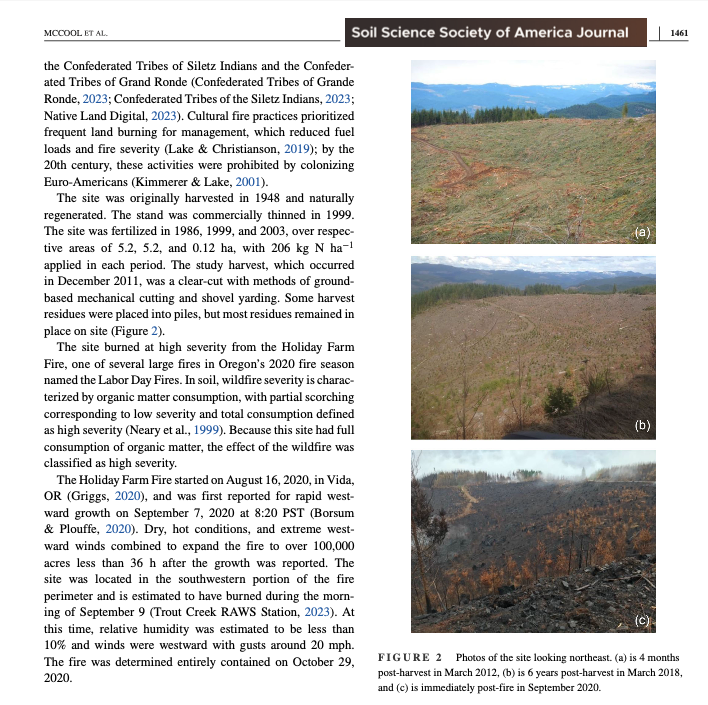

Forest soils of the Pacific Northwest contain immense amounts of carbon (C). Increasing acreage burned by severe wildfire in the western Oregon Cascades threatens belowground C stocks. The objective of this research was to quantify the changes in soil C stocks, nitrogen (N) stocks, and relevant chemical and physical parameters after a severe wildfire in a young, intensively managed Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas-fir) tree farm in the western Oregon Cascades. This longitudinal study was originally established to detect soil C changes after a harvest; therefore, it offers insight into long-term soil C dynamics after compounding disturbances. Forest floor and 0–30 cm depth soil samples were collected for comparison before and after the fire and were then split into size fractions to assess the fire’s effect on different grain sizes and forest floor compositions. Overall, soil C was approximately 40 Mg C ha−1 lower after the fire, equivalent to approximately 30% of soil C stocks. Of these decreases, two-thirds were in the forest floor and one-third were in the mineral soil. C stock losses were driven by changes in mass in every composite level. C concentration was unchanged in most levels while N concentration increased in certain levels. Losses extended further belowground than most previously studied soil C decreases from severe wildfire. The effects of wildfire on soil C stocks in industrial tree farms should be further explored to determine long-term trajectories of soil C and N.

TLDR

What happens when a bunch of young trees that are all touching each other get caught up in a massive windstorm and a bunch of utility poles fall down and start a fire? It’s bad, mmk!

Before getting into the heart of this paper, it’s worth learning about the history of fire suppression in the United States. This video is the best way to explain it, but the short version is that European colonizers in North America were pretty scared of fires. Beginning in the early/mid 1900’s the newly formed Forest Service was tasked with stopping all fires, and they’ve been incredibly successful. About 90% of all wildfires since then have been contained to <10 acres, just a small fraction of wildfires actually get big. Because we’ve prevented any fires from occurring over the last ~110 years, our forests have become “over-stocked” with trees.

Your standard landscape ecology textbook will have fire as a natural part of the ecosystem function, but when you eliminate fire you allow trees to grow in all the places they never used to grow; instead of seeing canopy gaps and meadows on mountain tops, everything got covered in trees. Wildfires would naturally thin out these trees, so there was more spacing between each tree allowing them easier access to water and nutrients.

Now-a-days, after a 100 years of fire exclusion, trees have a continuous canopy coverage, and they’re fighting for water and nutrient resources more than they ever had to in the past. With the advent of longer and more intense droughts due to climate change, there are too many trees fighting for too few nutrients and water, that are all touching branch to branch for thousands of acres. Remember, these forested ecosystems were accustomed to seeing fires somewhat often (1-3 years for oak-savannas, 3-5 years for Ponderosa pines, >50yrs for Douglas-fir, etc..). In a (continental scale project), we showed that pyrogenic carbon (partially burned organic matter) was present across all ecosystems and even in soils down past a meter in depth; just more evidence that fires have always been a critical piece of ecosystems. Ok, with that background in mind, what happens to an industrial timber plantation when a fire roars through?

Industrial (or intensive) forest management generally has the goal of producing wood products and wood products exclusively. The Forest Service (no matter how many environmental NGO’s scream about this) does not manage public lands in this way. Sure, they have areas for timber production, but it’s never the exclusive goal on public lands. Only private companies and private landowners can really manage forests this way.

The management strategies includes: high density planting (>300 trees per acre) usually with a herbicide application, one early rotation mechanical thinning, sometimes a mid-rotation thinning treatment, and usually 1-2 fertilizer applications over the 30-40 year timeline. I taught a whole class on the reasons for these strategies, but basically it’s more economical and you get higher quality wood products out of it.

I often say forestry is just slow agriculture (there’s a reason Weyerhaeuser calls their lands “tree farms”), and that’s a half-decent metaphor. Regardless, forestry and agriculture’s primary enemy is soil erosion. On farms soil erosion happens every single day. In forests it mostly only happens after a disturbance event (landslide, high intensity wildfire, road failures). The thing about soil erosion, is that because the overwhelming majority of soil nutrients and soil carbon are in the upper few centimeters, losing just a tiny bit of soil off the top amounts to most of the site nutrition. Growing trees, or any vegetation, becomes much harder because conditions are harsher.

In a high severity wildfire (where tree mortality exceeds >80%), soil burn severity is also typically high - leaving bare exposed mineral soil vulnerable to erosion. On this very young tree farm, there was a hell of a lot of erosion post fire. Sure you can kinda ameliorate the soil nitrogen losses (by gaseous losses and erosional) with fertilization, but that only really happens in industrial forests. And losing 30% of your site nitrogen is just too expensive and unrealistic to try and replace with fertilization.

Luckily, these soils are super duper resilient. While this is a different location than my Masters project, the soils are close to identical (andic influenced, low rock fragment, inceptisol). A fores will be able to re grow here, as is the case for the majority of the 10,000,000 acres that burned in the west during 2020. But not all places will look the same they did before. In fact they probably shouldn’t.

Remember, we excluded fire for >100 years, this fire seasion was a pretty hard ecosystem reset for many places. Post fire (assuming you don’t get too much erosion) generates incredible wildflowers and can produce many meadows. That early seral habitat (meadows, grasses, flowers) is in desperate short supply in the west because fires used to maintain their presence by killing the encroaching conifers. No fire means conifers encroached and closed up most of the meadow habitat. So there your glass half full. Huge massive wildfires kinda suck, but it’s what the ecology of the PNW and Rocky Mountain forest would dictate, and they provide flowers.